Existential Chaos

Coping with Existential Chaos

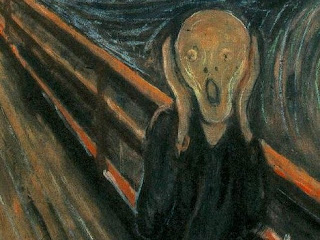

How do we hold on to meaning and purpose when the possibility of death is constantly in view? How can we believe in a just world when the world is patently unjust? How can we grasp the truth when the nature of truth itself is in doubt?

Religious and philosophical thinkers have obsessed over

these questions for millennia; existentialists have made them a primary concern over the past two centuries. In his seminal work Existential Psychotherapy (1980), the American psychiatrist Irvin Yalom categorised our existential problems into four ultimate concerns: death, freedom, existential isolation, and meaninglessness. We want to live, but we know we will eventually die. We have the freedom to make choices, but there is no absolute truth to ground these choices. We want to feel connection, but we feel alone in our subjective experience. We want our lives to be meaningful, but there appears to be no inherent meaning in the Universe.Awareness of these concerns gives rise to anxiety that we must manage; the defence mechanisms for doing so can be conscious or unconscious. A basic tenet of existential therapy is that how we manage this anxiety is intimately tied to our emotional wellbeing. Someone might try to avoid awareness of death by compulsively throwing themselves into the well-worn distractions of work, sex, drugs, fitness or any other activity that keeps them busy. Another might try to avoid awareness of freedom by staying with a romantic partner who controls their decision making and limits their autonomy. Yet another avoids existential isolation by blindly conforming to their ingroup and denigrating or attacking the other.

In existential psychotherapy, the role of the therapist is to assist the client in confronting these ultimate concerns to find more adaptive responses. Perhaps counterintuitively, the existential therapist’s goal is not necessarily to decrease anxiety or depression, but rather to create a safe and supportive environment for the client to explore their existential conundrums and, in so doing, work through their symptoms to develop their own answers to life’s ultimate questions.

Three years ago, I left my family and a good job back in Australia to pursue graduate school in the United States and study the utility of existential ideas in science-based clinical psychology. This pursuit led me to terror management theory (TMT), the leading empirical social psychological theory on how humans cope with their awareness of mortality. Based on the writings of the American cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker, especially his book The Denial of Death (1973), TMT begins with the core human existential problem of wanting to live while simultaneously knowing that death is inevitable. People can initially defend against potentially overwhelming fear of death by engaging in conscious, pseudo-rational strategies directed at neutralising the problem of death. People can distract themselves, suppress death-related thought, or rationalise death away by focusing on how healthy they are.

Once outside of conscious awareness, we can buffer against these death-related thoughts by implicitly striving for a sense of permanence and meaning. By adopting and meeting the standards of worth set by our culture, we attain self-esteem and feel part of an enduring cultural reality that outlasts our finite lives. Religion can offer a sense of literal immortality; ideology, nation, legacy or children can provide a sense of symbolic immortality.

The existential issues were no longer hiding under the surface of career path or relationship discussions: they were splashed all over the news

TMT is supported by thousands of studies and is consistent with Yalom’s contention that humans engage in defence mechanisms to avoid thoughts about death. However, I wondered whether there was room in TMT for the existential therapist whose mission is to bring death – or any other ultimate concern for that matter – to conscious awareness as a catalyst for positive personal growth and transformation. Throughout history, thinkers from Seneca to Heidegger have recommended keeping death in conscious awareness to remind us how short life is, and thus motivate us to live as authentically and as fully as possible. When you come to understand and deeply engage with the fact that your life is finite, would you choose to spend it differently? Would you continue chasing others’ expectations, being what your parents, partners or friends always expect of you, or would you embrace the fear of human existence and live according to your own hopes and dreams? Would you continue to curse the state of the world, or would you open your eyes to the beauty that’s all around you? Would you continue to lament what you don’t have, or appreciate and savour the people you love and who love you?

As I reflected on these questions in graduate school, it occurred to me that many college students have no venue – other than late-night conversations in the dormitories – and few opportunities to sit with and explore Yalom’s ultimate concerns, let alone the defences that organise their lives. When I was asked to co-facilitate an existential therapy group for college students at our university counselling centre, where I worked as a therapist trainee, I was thrilled and encouraged to draw on all my training and the available scholarly literature on existential therapies. Scaffolding would be critical to help our young adult students gain a sufficient foothold before looking directly at the ultimate questions. We can refer to this kind of confidence and willingness to stare into the abyss as existential courage. Without this courage, we might continue to live life blind to the fundamental truths of our existence, inauthentically or, as the existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre put it, in ‘bad faith’. Could my willingness to go down this road be shared with college sophomores?

Our inaugural existential therapy group first met in February 2020. We were a diverse group of six undergraduates, two graduate students and two facilitators – a communion of fellow travellers navigating the big-picture questions in life. We discussed various existential issues common to college students – choosing a university major or a career path, how to make connections while maintaining one’s individuality, and so on. However, by March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was ramping up in the US, and we were forced to move our group online. The existential issues were no longer hiding under the surface of career path or relationship discussions: they were splashed all over the news and had infiltrated all corners of our collective consciousness.

‘What is wrong with the world?’ someone said.

Through laptops and phone screens, we all stared blankly, solemnly, at each other. The impact of the pandemic was now unavoidable – school closings, unemployment, hoarding, shortages, racism, death. The happenings evoked our worst anxieties and, even as the group’s co-facilitator and a doctoral student in clinical psychology, I wasn’t immune to the dread. Our newfound and computer-mediated reality was a poor substitute for in-person gatherings, perhaps even amplifying rather than quelling the dread. We were together, but very much apart.

What is wrong with the world?

These words echoed a sentiment shared by millions of people at a time of significant upheaval. Many had lost jobs, or even loved ones, and many more were isolated at home and mired in the unpredictability and uncontrollability of this novel coronavirus, searching for answers in 24-hour news, fake news, social media and increasingly polarised political discourse. Many were coming of age in this strange, socially distanced world, all the while hungering for deeper intimacies. Yearning for touch while staying six feet apart.

I prompted the group: ‘I get the sense that we all think there’s something wrong with the world right now. Is that correct? Okay, but what do we mean when we say there’s something wrong with the world?’ The answers poured out:

‘People are stupid.’

‘I can’t believe people are hoarding, they’re so selfish.’

‘Why aren’t people staying at home? They’re only prolonging this crisis.’

‘I don’t know what to believe any more.’

‘I took for granted that the world would be a certain way.’

‘Someone gave me dirty looks because I’m Asian.’

These were bedrock issues surrounding ultimate concerns. ‘Okay, and how are we feeling about all that?’ I asked.

‘I feel anxious.’

‘It makes me sad.’

‘I’m scared.’

‘I feel hopeless.’

‘I’m confused.’

‘I’m frustrated.’

‘I’m angry.’

‘Those thoughts and feelings make sense,’ I replied. ‘The world is in chaos right now, some people are acting selfishly and awfully, and we don’t know when or even if things will return to normal. There is so much we cannot control.’

Too much doom and gloom? Too much meaninglessness? Strangely, I am more optimistic than ever

At this moment, I thought of Viktor Frankl, the Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor who observed that it was always possible – and necessary – to strive for meaning, even in the face of immense suffering and despair. With Frankl in mind, I responded: ‘But we can still choose how we react to this situation, even if we’re forced to stay at home. In fact, we can still choose our attitude in any given situation. How would you like to react to this pandemic? What kind of person would you like to be?’

‘I would like to be kind.’

‘I want to comfort others.’

‘I would like to reconnect with my friends and family.’

‘I am more appreciative of what I have.’

‘I want to be strong and resilient.’

‘It seems we all have a choice to make,’ I pointed out. ‘We can choose to blame others and to complain about the state of the world, which seems easier. Or we can channel that energy into taking personal responsibility and making positive changes in our lives and the lives of others, which seems harder. Which will it be?’

We ended the session by agreeing to reach out and reconnect with someone we haven’t spoken to in a while, comforting them in these difficult times if we could.

Drawing out and highlighting existential themes in the group’s discussion provided opportunities for reflection on the givens of existence. Faced with trying circumstances, people can easily lose sight of their existential freedom and responsibility. From there, the fall into despair and cynicism is as easy as slipping off a wet rock. Holding people accountable to life’s ultimate questions is the core of existential psychotherapy, the foundation for real transformation, and perhaps a secret key for authentic living.

Having co-led this existential therapy group of college students for four months, mired in the ultimate concerns, you might have reason to worry about my mental health. Too much doom and gloom? Too much meaninglessness? Strangely, I am more optimistic than ever. I would be lying if I did not confess my initial skepticism about an existential therapy group for undergraduates – how could young people have the life experience to adequately contemplate such big questions? I often reflect on my own upbringing and the ubiquity of tragedy and suffering – those great harbingers of existential dilemmas; these seeds of the big questions are unmistakably present among all young people. No doubt the collective trauma brought on by the pandemic only serves to bring the tragedy of the human condition to the forefront of all our minds as well. Despite this trauma, I was inspired and even amazed by the students’ existential courage and willingness to wrestle with the challenging questions in life. In facing and very plainly dissecting the terrifying truths of existence, we became stronger, more resilient and more capable of taking control of our lives and sailing toward new horizons. Can we really afford to keep living as if we’ll live forever?

Ronald Chauis a graduate student in clinical psychology at the University of Arizona.

https://psyche.co/ideas/existential-psychotherapy-helped-my-students-cope-with-chaos

The Work of Victor Frankl on creating meaning in chaos

With our collapsing democracies and imploding biosphere, it’s no wonder that people despair. The Austrian psychoanalyst and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl presciently described such sentiments in his book Man’s Search for Meaning (1946). He wrote of something that ‘so many patients complain [about] today, namely, the feeling of the total and ultimate meaninglessness of their lives’. A nihilistic wisdom emerges when staring down the apocalypse. There’s something predictable in our current pandemics, from addiction to belief in pseudoscientific theories, for in Frankl’s analysis, ‘An abnormal reaction to an abnormal situation is normal behaviour.’ When scientists worry that humanity might have just one generation left, we can agree that ours is an abnormal situation. Which is why Man’s Search for Meaning is the work to return to in these humid days of the Anthropocene.

Already a successful psychotherapist before he was sent to Auschwitz and then Dachau, Frankl was part of what’s known as the ‘third wave’ of Viennese psychoanalysis. Reacting against both Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, Frankl rejected the first’s theories concerning the ‘will to pleasure’ and the latter’s ‘will to power’. By contrast, Frankl writes that: ‘Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation in his life and not a “secondary rationalisation” of instinctual drives.’

Frankl argued that literature, art, religion and all the other cultural phenomena that place meaning at their core are things-unto-themselves, and furthermore are the very basis for how we find purpose. In private practice, Frankl developed a methodology he called ‘logotherapy’ – from logos, Greek for ‘reason’ – describing it as defined by the fact that ‘this striving to find a meaning in one’s life is the primary motivational force in man’. He believed that there was much that humanity can live without, but if we’re devoid of a sense of purpose and meaning then we ensure our eventual demise.

https://aeon.co/ideas/what-viktor-frankls-logotherapy-can-offer-in-the-anthropocene

Comments

Post a Comment