Critical Race Theory

Conservative white Christian activists across the country have been on a book-banning crusade, labeling publications that tell the truth about race in America as dangerous “critical race theory” texts.

I’ve been teaching on race and racial healing for nearly three decades, and I never knew what critical race theory was until two years ago, when the political right turned it into a bogeyman posing a grave threat to America herself. It didn’t take much research to find out the right-wing had predictably twisted CRT beyond recognition to serve their political aims.

No surprise there.

But what did surprise me is how perfectly this decades-old legal-theory-turned-culture-war-fodder described the lived experience of 10 generations of my family, from the late 1680s, when Maudlin Magee and Sambo Game arrived on the eastern shores of the Colony of Maryland as indentured and enslaved persons, all the way up to my life today.

This simple yet profound theory called CRT was developed during the 1970s, when the vast majority of legal scholars failed to recognize the impact race has had in shaping the systems that govern American society. Black scholars argued that race was a legal construct so deeply embedded in America’s legal structures that many people couldn’t see what was right in front of their faces: a system that disenfranchises and oppresses whole people groups while claiming to provide justice and equality for all. CRT is not being taught in grade schools and is rarely taught anywhere outside of law schools. That said, these legal scholars crafted a theory proven true by the lives and stories of African American families.

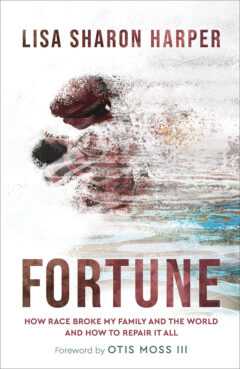

“Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World and How To Repair It All” by Lisa Sharon Harper. Courtesy image

This is exactly what I found when I delved deep into my family’s storied history for my new book “Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World — And How To Repair It All.” Race, and the impacts of America’s legal and political construct, are the lived realities of my family. We cannot get away from it. Race has inextricably and mercilessly shaped the course of our lives and our fortunes. To ignore this is to ignore reality.

Mixed-race Fortune Game Magee (b. 1687) was my first American-born ancestor. Fortune’s half-Senagalese, half-Ulster Scots body could not evade the power of the newly constructed legal and political framework called race, first conceived by Plato, pontificated on by Aristotle, entrenched by Pope Nicolas V and the botanist Carl Linnaeus and embedded into Colonial Maryland’s legal framework only 23 years before Fortune’s birth.

Fortune stood alone in a country courtroom on Colonial Maryland’s eastern shore in 1705. Here her mixed-race body bore the wrath of the first round of race laws hatched on American soil. Those laws shaped the course of her life and the lives of all of her descendants.

The first iteration of Maryland’s race laws demanded the enslavement of white women who married and had children with enslaved African men. But, by the time Fortune stood in that courtroom, Maryland’s legislature had backtracked on white women’s enslavement and declared, instead, that the offending white woman was to be indentured for seven years and could not be enslaved — because she was white. Nor could her children be enslaved — because she was white. Rather they would be indentured for up to 31 years, depending on the circumstances of the mixed-race child’s birth. The first flashes of white privilege were explicit and precise in our nascent colonial years.

So, Fortune, the daughter of Sambo Game and Maudlin Magee, was indentured until she was 31 years old, in accordance with the law. And two generations of her descendants were also indentured — DNA evidence coupled with scholarship on the use of rape to dominate in the colonial era reveals they were likely the products of sexual assault by the men of their indenturing families, increasing the profit margins of white men by breeding free labor, bound to them for decades by law.

On every branch in every era of my family’s history, laws were crafted to do one thing: establish, protect and preserve white male money and power. This was true for my great-great-grandparents, Henry and Harriet Lawrence, whose family stories intersected with both slavery and the Cherokee and Chickasaw removals. They suffered the confusion of identity as racial constructs were reformed after the Civil War. This was true for my great-grandmother, Lizzie Johnson, driven north in the Great Migration to escape South Carolina’s suffocating race laws, which prohibited people of African descent from working in any other sector than the fields or domestic labor.

This was true for my mother, Sharon, who sat in a de facto segregated school in Philadelphia and received hand-me-down books from the white school two blocks from her house. My mother’s white next-door neighbor attended Drexel School, but the school was declared “out of district” for her. It was true for me: My Christian faith was born the very same year that Bob Jones University argued before the Supreme Court to maintain pure white space. They lost, and in response the Religious Right was spawned, declaring its primary strategy to shift the ideological makeup of the Supreme Court.

When I began my research into my family’s 340-year history on this land, I simply set out to understand who I am. In the course of that journey, I discovered who we are as a nation. America is smothered under a canopy of laws, structures and policies, never fully repented and atoned for, explicitly and implicitly intent on maintaining white male dominance.

This is the truth. Which is why my book stands a very good chance of being banned. My family’s story — which is the story of so many Black American families — challenges the myths of inherent white nobility, goodness and rightness. It reveals the constant drumbeat of war that undergirds the symphony of America, regardless of party or ideology — the war for white male power. It calls for truth-telling and reparation. Perhaps most radically, it calls for what Dr. Martin Luther King called The Beloved Community. I, and so many Americans, yearn for the transformation of our nation into a place where all of us are able to flourish.

Lisa Sharon Harper. Photo by Joy Guion Bailey

This is exactly the kind of America the book-banners fear.

(Lisa Sharon Harper is the founder of Freedom Road, a consulting group dedicated to shrinking the narrative gap. She is the author of several books, including her most recent Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World — and How to Repair It All. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Comments

Post a Comment